The study, “A BMI >35 does not protect patients undergoing cardiac bypass surgery from red blood cell transfusion,” was the first to reveal differences in the relationship between blood transfusion rate and obesity by category. It published January 1, 2017, in Perfusion.

CLINICAL ISSUE

Obesity is a recognized risk factor for numerous health conditions, but, paradoxically, substantial evidence suggests excessive weight may have a beneficial effect on cardiac surgery outcomes. However, the influence of obesity on the risk of intraoperative red blood cell transfusions in patients undergoing coronary artery bypass graft (CABG) surgery is poorly understood.

A research team, led by SpecialtyCare’s medical department in Nashville, Tennessee, recently looked at the effect of obesity on this specific risk by conducting a retrospective analysis of data on 45,200 CABG procedures performed at 198 institutions. Their novel finding throws the “obesity paradox” into question for blood transfusions, which warrants further investigation with prospective, randomized clinical trials.

STUDY DESIGN

Case records on patients operated on between April 2013 and April 2015 were drawn from the SpecialtyCare Perfusion Data Registry and excluded non-isolated CABG procedures and reoperations.

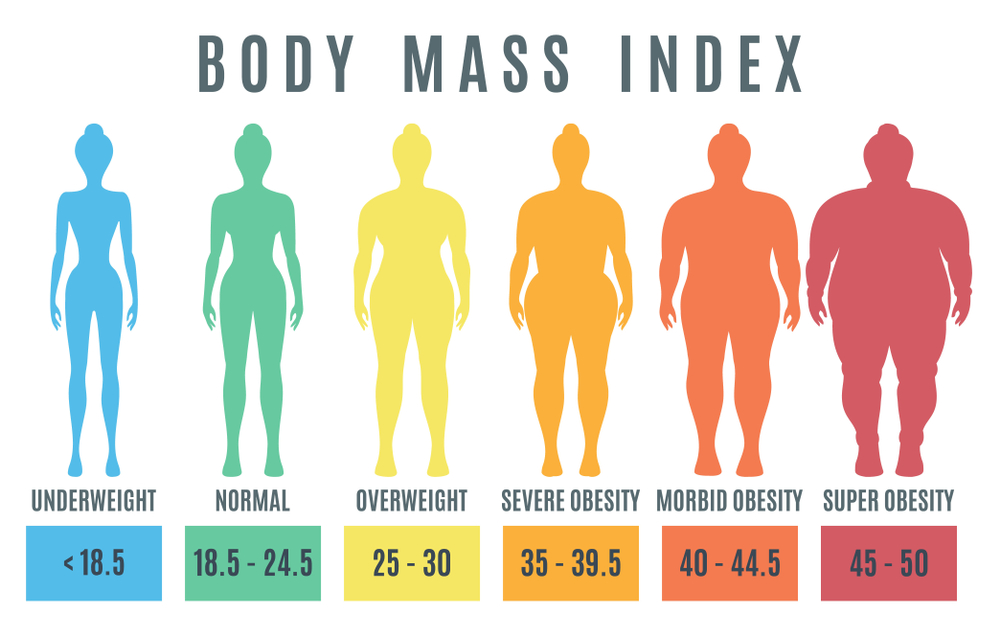

Patients were grouped into one of six body mass index (BMI) categories, as defined by the World Health Organization (WHO): underweight (BMI<18.5), normal weight (BMI 18.5 to 25), overweight (BMI 25 to 30), obese I (BMI 30 to 35), obese II (BMI 35 to 40), and obese III (BMI>40). Among patients in the final sample, 43.8 percent fell into one of the three WHO categories for obesity.

Using binary logistic regression, the research team predicted the risk of transfusion for each BMI category relative to normal weight patients. Their analysis controlled for 13 known confounding variables, including age, gender and inherent riskiness of the procedure. Transfusion was defined as the administration of one or more red blood cell units during surgery.

KEY FINDINGS

Obese II and obese III patients had no change in their transfusion risk relative to patients with a normal BMI after adjusting for all the confounding variables. A decrease in transfusion risk was seen for patients in the obese 1 group (9.9 percent), but to a lesser extent than with patients in the “overweight” category (14.3 percent).

EXISTING EVIDENCE

Many published papers support the theory that overweight and obese patients have better outcomes after cardiac surgery than their normal-weight counterparts. Most investigators also have not found obesity to be an independent risk factor for mortality after cardiac surgery.

On the other hand, it has been postulated that the weight-based calculations typically used for estimating blood volumes could be causing patients with excess body fat to become oxygen-deprived during cardiopulmonary bypass. This might help explain why obese patients have been found to have more than double the risk of severe respiratory impairment than non-obese patients in the intensive care unit following surgery.

BMI does not accurately depict different components of body composition. In obese people, unlike normal-weight individuals, fat and lean body mass do not go up in harmony. Obese patients might have low, normal or high lean body mass, and there is as yet no reliable measurement tool to tell one from the other. Visual observation alone is insufficient except, perhaps, for patients who are obviously fit and athletic.

It is widely recognized that many other factors beyond BMI influence cardiac surgery outcomes over which clinicians have no control; they nonetheless need to be taken into consideration. For example, being young and male can have a protective effect. Overestimating patients’ blood volume based on obesity can also potentially throw off calculations for how much clear fluid needs to be added to their circulating blood and what proportion of it needs to be rerouted to apparatus outside the body during cardiopulmonary bypass. Additionally, complex cardiac procedures requiring a longer time on the heart-lung machine raises the risk of having a blood transfusion.

CLINICAL EXCELLENCE IN PRACTICE

With increasing obesity, the protective benefit of the extra pounds diminishes when it comes to blood transfusion risk. Accurately identifying patients’ true body type is also a daunting task. In the absence of a reliable yardstick, calculating the blood volume of morbidly obese patients can be especially tricky—and overestimating can result in under-dosing of clear fluids and blood products should a hemorrhage occur.

Given that high BMIs are at a record high in the U.S., clinical teams will want to guard against a false sense of security about the transfusion risk of obese patients during cardiac surgery. Overall, the unique makeup and needs of this growing population require closer attention. Adjustments may be needed during cardiopulmonary bypass, since obese patients tend to have low oxygen ratios postoperatively that may indicate pre-existing respiratory dysfunctions. Leptin, a protein secreted by fatty tissue, has also recently been associated with thrombosis (blood clot) and that risk would need managing before surgery begins.

THE RESEARCH TEAM

The study team for this research included five members of the SpecialtyCare Medical Department—Linda B. Mongero, BS, CCP; Eric A. Tesdahl, PhD; Alfred H. Stammers, MSA, CCP; Timothy A. Dickinson, CCP; and Samuel Weinstein, MBA, M.D.—established to maintain a quality-first focus on all clinical matters at the organization. They were joined by Alan P. Kypson, M.D., a cardiothoracic surgeon affiliated with UNC Health Care in Chapel Hill, North Carolina, and John Brown, M.D., a thoracic and vascular surgeon affiliated with Morristown Medical Center in Morristown, New Jersey.

Comments are closed.